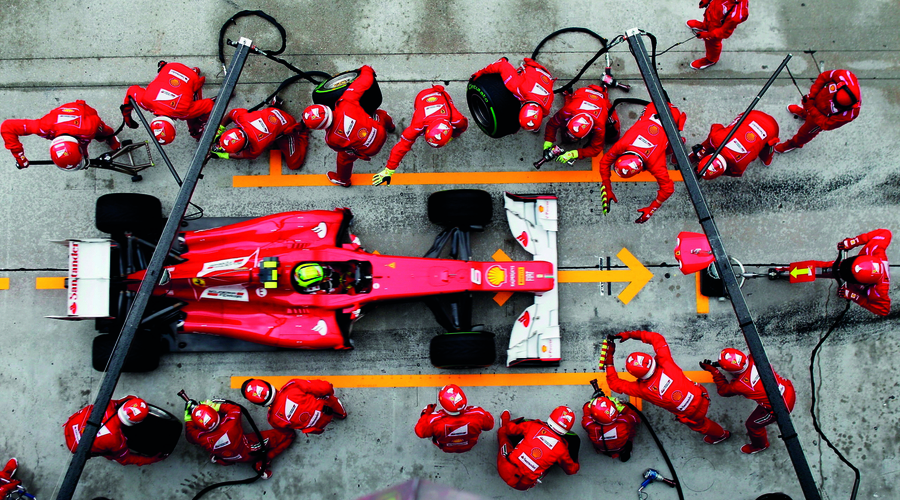

Can Liberty Media modernise Formula One for an audience addicted to social media? Owen Gibson is our man in the pits.

When Bernie Ecclestone’s reign as Formula One’s ringmaster finally came to an end earlier this year, it was accompanied by a frisson of disbelief. Until that moment, it had felt as though the former used-car salesman who had built Formula One from a disparate cottage industry into an $8bn business was indivisible from the sport he bestrode.

But, in taking the decision to oust the 86-year-old from a meaningful management role, the sport’s new owner – Liberty Media – was underlining its intention to modernise a product whose appeal appeared to be flatlining.

For a sport that has always built its allure on an intoxicating mix of romance and technology, there were signs that its star was on the wane.

Shortly before agreeing the deal that saw Liberty Media acquire the sport under moustachioed supremo Chase Carey, Ecclestone admitted that it had lost a third of its viewership since 2011.

In simple terms, 200 million people worldwide had turned their backs on Formula One. This could partly be accounted for by Ecclestone’s strategy of moving the sport from free-to-air to pay-TV; sponsors preferred the former because it gave them more exposure.

But many of those within, or around, the sport’s hermetically sealed bubble believed that there was also something more fundamental at play.

“I don’t know why people want to get to the so-called ‘young generation’. Why do they want to do that? Is it to sell them something? Most of these kids haven’t got any money."

Ecclestone had successfully built Formula One on a combination of horse trading and ruthless control. But was that approach still suited to the new world of abundant access across multiple digital channels and online platforms via a dizzying array of devices?

While always keen to experiment with new models if he saw a financial upside – recall the abortive attempt to establish an interactive F1 subscription channel before the technology was ready – Ecclestone could appear all at sea in the digital world.

Two years previously, he had waved away suggestions that his sport needed to boost its youth appeal.

“I’m not interested in tweeting, Facebook and whatever this nonsense is,” said Ecclestone in 2014. “I tried to find out but, in any case, I’m too old-fashioned. I couldn’t see any value in it. And, I don’t know what the so-called ‘young generation’ of today really wants. What is it?”

Ecclestone’s view was that the sponsors that bankrolled his sport were looking to target older fans who would buy their luxury brands. But that ignored two things.

First, that social media and digital channels are now increasingly ubiquitous for all ages; and, second, that a sport built on perpetual motion has to be seen to be moving forward. Instead, it risks coasting to a standstill.

“I don’t know why people want to get to the so-called ‘young generation’. Why do they want to do that? Is it to sell them something? Most of these kids haven’t got any money,” said Ecclestone then. “I’d rather get to the 70-year-old guy who’s got plenty of cash.

“So, there’s no point trying to reach these kids because they won’t buy any of the products here and, if marketers are aiming at this audience, then maybe they should advertise with Disney.”

By the standard of some of his other pronouncements – Ecclestone had previously sung the praises of Vladimir Putin and said that Adolf Hitler was someone who “got things done” – it was hardly controversial.

(Credit: Ryan Bayona/WikiCommons)

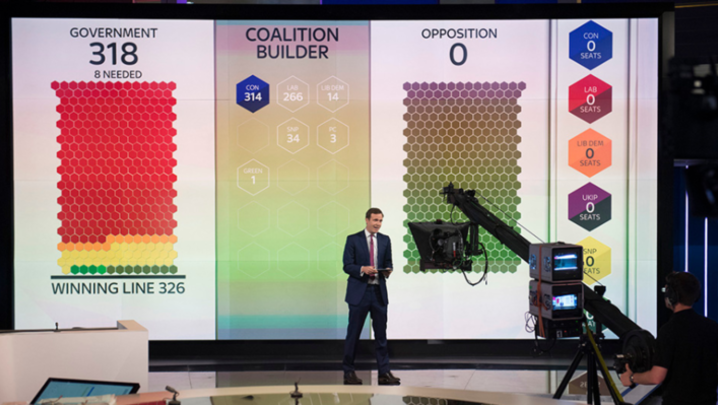

In the UK, Formula One had gone from a sport on which the BBC was prepared to lavish £40m a year in 2009 – and thereby resist the relentless trend for sport’s glitziest properties to head towards pay-TV – to one that the corporation was happy to pass on, in order to save cash. The BBC launched its coverage at the height of Lewis Hamilton’s first flush of fame following his inaugural title win. The broadcaster presented it as a means of targeting hard-to-reach demographics, including younger men.

But it rapidly became clear that, in line with Ecclestone’s later comments, Formula One’s audience was an ageing one – albeit a committed and moneyed fan base. All of which, in fact, made it an attractive target for pay-TV.

First, the BBC decided to relinquish half of the races, ending its deal with Ecclestone early, to share rights with Sky. The corporation subsequently relinquished the rest of its rights, which were picked up by Channel 4. To complete the switch to pay-TV, Sky then scooped the rights exclusively from 2018.

But Liberty’s avowed intention is to reverse the flow, democratise the sport, take it to new fans and subtly effect a shift from a product that is wringing ever more money out of a contracting audience to one striking out for new audiences.

All of which is, of course, easier said than done in an ever-more crowded media and sporting landscape.

Having appointed former ESPN executive Sean Bratches to oversee the sport’s commercial growth, much of Liberty’s early rhetoric has been concerned with the sport’s digital reach. It may be significant that Norman Howell, the man Bratches appointed head of global communications, was formerly head of Formula One’s digital channels.

“We want fans to get closer to the action on and off the track, with new levels of entertainment and engagement. If we can do this, Formula One will continue to be one of the biggest sporting brands in the world,” says Howell.

In an early hint of what may follow, one of Liberty Media’s first steps was to relax the social-media restrictions around the sport. Indeed, it seems an obvious move to make if the company wants to build deeper bonds between the drivers and fans, and promote the personalities behind the helmets.

Hamilton, for one, complained last season that the endless rounds of top-table appearances were “boring”. He preferred to communicate directly with fans via Instagram and Snapchat. One divisive episode summed up the sport’s cultural collision: half of the fanbase praised Hamilton, as he fiddled with his phone like a bored teen during a press conference while the other half castigated him.

But, crucially, it got people talking. Part of Liberty’s plan is to reconnect casual audiences and general sports fans with the glamour, drama and personality of the sport.

Previously, contractual restrictions prevented drivers and teams from posting video content from the paddock. Predictably, Hamilton was among the first to take advantage of the new rules, with the Mercedes driver posting content from the testing track in Barcelona.

Digital engagement alone won’t reverse declining viewing trends but Liberty – which did, after all, shell out $8bn on the show that Bernie built – is convinced that, if it can add a modern twist to the deep bonds that petrolheads have with their sport, it will be on to a winner.

Under Carey, the highly respected Ross Brawn, recently appointed as Formula One’s Managing Director of Motorsport, has been charged with innovating the sport. Meanwhile, Bratches takes care of spearheading the commercial and media side.

Structurally, everything from shorter races to new city-centre-based locations have been mooted. In his first round of interviews, Carey stated simply: “We’re not marketing the sport.”

Expect that to change. But, in a global media and sporting landscape that often feels like it is spinning faster than a Pirelli Slick, innovating while maintaining its allure to the broadcasters – who have traditionally brought in its biggest audiences and revenues – will be no mean feat.

Like the sport itself, it promises to be a thrilling ride for Liberty, but one fraught with jeopardy.